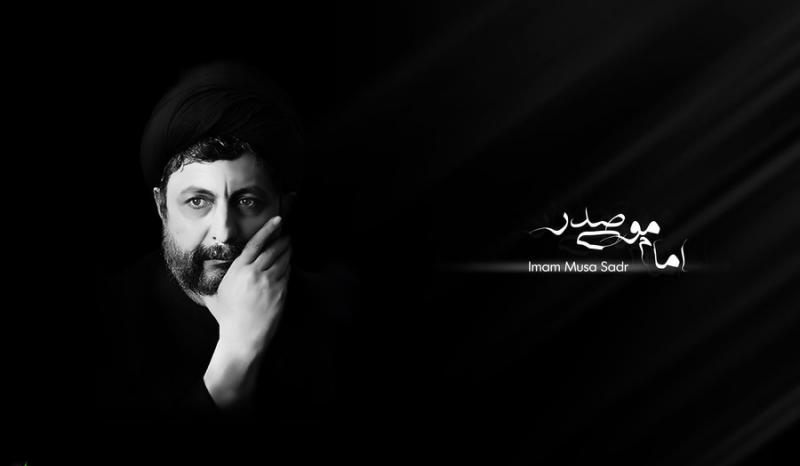

Imam Musa as-Sadr was born in Qom, Iran, on 4 June 1928 to the prominent Shia Lebanese aṣ-Sadr family of theologians. His father was Ayatollah Sadr al-Din Sadr, originally from Lebanese city of Tyre and a marja-i taqlid in Iran. His grandfather, Sayyed Ismail Sadr, was born in Lebanon and a leading marja-i taqlid in Iraq. Grand Ayatollah Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr was his first cousin.

Musa as-Sadr attended primary school in his hometown and then moved to the Iranian capital Tehran where he received a degree in Islamic jurisprudence (Fiqh) and political sciences from Tehran University. Then he moved back to Qom to study Theology and Islamic philosophy under Allamah Muḥammad Husayn Tabatabai. He then edited a magazine called Maktab-e Eslam in Qom. In 1953 following the death of his father he left Qom for Najaf to study theology under Ayatollah Muhsin al-Hakim and Abul Qasim Khui.

Imam Musa in Lebanon

In 1960, Musa as-Sadr accepted an invitation to become the leading Shi'i figure in the city of Tyre to succeed former Shi'i leader of the city, Abdul Hussein Sharafuddin, who died in 1957.

As-Sadr, who became known as Imam Musa, quickly became one of the most prominent advocates for the Shiah population of Lebanon, a group that was both economically and politically disadvantaged. He is said to have, "worked tirelessly to improve the lot of his community - to give them a voice, to protect them from the ravages of war and intercommunal strife."

As-Sadr was widely seen as a moderate, demanding that the Maronite Christians relinquish some of their power but pursuing ecumenism and peaceful relations between the groups. He was an opponent of Israel but did also criticize the PLO for endangering Lebanese civilians with their attacks.

In 1969, Imam Musa was appointed as the first head of the Supreme Islamic Shi'ite Council (SISC), an entity meant to give the Shia more say in government. For the next four years, he engaged the leadership of the Syrian Alawis in an attempt to unify their political power with that of the Twelver Shia. Though controversial, recognition of the Alawi as Shia coreligionists came in July 1973 when he and the Alawi religious leadership successfully appointed an Alawi as an official mufti to the Twelver community.

In 1974 he founded the Movement of the Disinherited to press for better economic and social conditions for the Shia. He established a number of schools and medical clinics throughout southern Lebanon, many of which are still in operation today. Al-Sadr attempted to prevent the descent into violence that eventually led to the Lebanese Civil War, but was ineffective. In the war, he at first aligned himself with the Lebanese National Movement, and the Movement of the Disinherited developed an armed wing known as Afwaj al-Muqwamat al-Lubnaniyya better known as Amal. However, in 1976 he withdrew his support after the Syrian invasion on the side of the Lebanese Front. He also actively cooperated with Mostafa Chamran, Sadegh Ghotbzadeh and other Iranian Islamist activists during the civil war. Al-Sadr rejected the Ayatollah Khomeini's interpretation of the Velayat-e Faqih. In addition Al-Sadr was instrumental in developing ties between Hafez Assad, then Syrian president, and the opponents of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Shah of Iran.

He was often a critic of the Shah of Iran, but it was only after the Yom Kippur (October) War of 1973 that his relations with the Shah deteriorated seriously. He accused the Shah of suppressing religion in Iran, denounced him for his pro-Israel stance, and described him as an "imperialist stooge." As Imam Musa's relations with Iran deteriorated after 1973, he improved his relations with Iraq, from which he may have received significant funding in early 1974.

Imam Sadr was tall, flamboyant and elegant and fluent in stylish Arabic. He was related to Ayatollah Khomeini by marriage. Khomeini's son, Ahmad, was married to as-Sadr’s niece, and as-Sadr’s son was married to Khomeini’s granddaughter.

Imam Sadr's last visit

On 25 August 1978, as-Sadr and two companions Sheikh Muhammad Yaacoub and journalist Abbas Badreddine departed for Libya to meet with government officials. The visit was paid upon the invitation of then Libyan ruler Muammar Gaddafi. The three were seen lastly on 31 August. They were never heard from again.

It is widely believed that Gaddafi ordered as-Sadr's killing, but differing motivations exist. Libya has consistently denied responsibility, claiming that as-Sadr and his companions left Libya for Italy. Sadr's son claimed that he remains secretly in jail in Libya but did not provide proof. as-Sadr's disappearance continues to be a major dispute between Lebanon and Libya.

Lebanese Parliament Speaker Nabih Berri claimed that the Libyan regime, and particularly the Libyan leader, were responsible for the disappearance of Imam Musa Sadr, London-based Asharq Al-Awsat, a Saudi-run pan-Arab daily reported on 27 August 2006.

According to Iranian General Mansour Qadar, the head of Syrian security, Rifaat al-Assad, told the Iranian ambassador to Syria that Gaddafi was planning to kill as-Sadr. On 27 August 2008, Gaddafi was indicted by the government of Lebanon for al-Sadr's disappearance. Following the fall of the Gaddafi regime, Lebanon and Iran appealed to the Libyan rebels to investigate the fate of Musa al-Sadr.

In an interview political analyst Roula Talj said that the son of Gaddafi, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, told her that Imam Musa Sadr and his aides, Mohammed Yaqoub and Abbas Badreddin, never left Libya.

According to representative of Libya’s National Transitional Council in Cairo, Gaddafi murdered Imam Musa Sadr after discussion about Shia beliefs. Imam Musa Sadr accused him of unawareness about Islamic teachings and about the Islamic branches of Shia and Sunni, following which Gaddafi became enraged and ordered the murder of Imam Musa Sadr and his accompanying delegation. According to other sources the murder of Musa al-Sadr was done by Muammar Gaddafi, they claim, at request of Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat. The Shias and the Palestinians at that time were involved in armed clashes in Southern Lebanon.

According to a former member of the Libyan intelligence, as-Sadr was beaten to death for daring to challenge Gaddafi at his house on matters of theology. In an interview with Al-Aan TV Ahmed Ramadan an influential figure in the Qaddafi regime and an eye witness of the meeting between al-Sadr and Qaddafi, mentioned that the meeting lasted for two and a half hours and ended up with Qaddafi saying "take him". Ramadan also named three officials who he believes were responsible for the death of as-Sadr. When Ahmed Jibril who had a strong relationship with Gaddafi asked him about these allegations, Gaddafi denied them saying he had no reason to kill Musa al-Sadr.

Imam Musa the Prominent Islamic Philosopher

Imam Musa as-Sadr is still regarded as an important political and spiritual leader by the Shia Lebanese community. His status only grew after his disappearance in August 1978, and today his legacy is revered by both Amal and Hezbollah followers. In the eyes of many, he became a martyr and "vanished imam." A tribute to his continuing popularity is that it is popular in parts of Lebanon to mimic his Persian accent. The Amal Party remains an important Shi‘ah organization in Lebanon and looks to as-Sadr as its founder.

Musa as-Sadr has been referred to by professor and writer Fouad Ajami as a "towering figure in modern Shi'i political thought and praxis." According to him, even American diplomats effusively described Musa Sadr after meeting him. He supports his claim by referring to a cable sent home by George M. Godley, a U.S. ambassador to Lebanon: "He is without debate one of the most, if not the most, impressive individual I have met in Lebanon. . . . His charisma is obvious and his apparent sincerity is awe-inspiring". In Lebanon, he had garnered significant popularity "due to his good rapport with young people."

Imam Sadr is most famous for his political role, but he was also a philosopher. According to Professor Seyyed Hossein Nasr, "His great political influence and fame was enough for people to not consider his philosophical attitude, although he was a well-trained follower of long living intellectual tradition of Islamic Philosophy."

SOURCES:

-

Arbaeen 2017: Pilgrims Flocking to Karbala for Arbaeen (PHOTOS)

Arbaeen 2017: Pilgrims Flocking to Karbala for Arbaeen (PHOTOS)

-

Ashura 2016: The annual Ashura day procession in London (PHOTOS)

Ashura 2016: The annual Ashura day procession in London (PHOTOS)

-

Arbaeen 2016: World Shiite Muslims Commemorate Arbaeen (PHOTOS)

Arbaeen 2016: World Shiite Muslims Commemorate Arbaeen (PHOTOS)

-

Ashura 2017: Thousands of Muslims march on Ashura day in London (PHOTOS)

Ashura 2017: Thousands of Muslims march on Ashura day in London (PHOTOS)

-

Arbaeen 2015: Millions of pilgrims throng Iraq's Karbala (PHOTOS)

Arbaeen 2015: Millions of pilgrims throng Iraq's Karbala (PHOTOS)

Library

Library